5.1: Packs on Backs

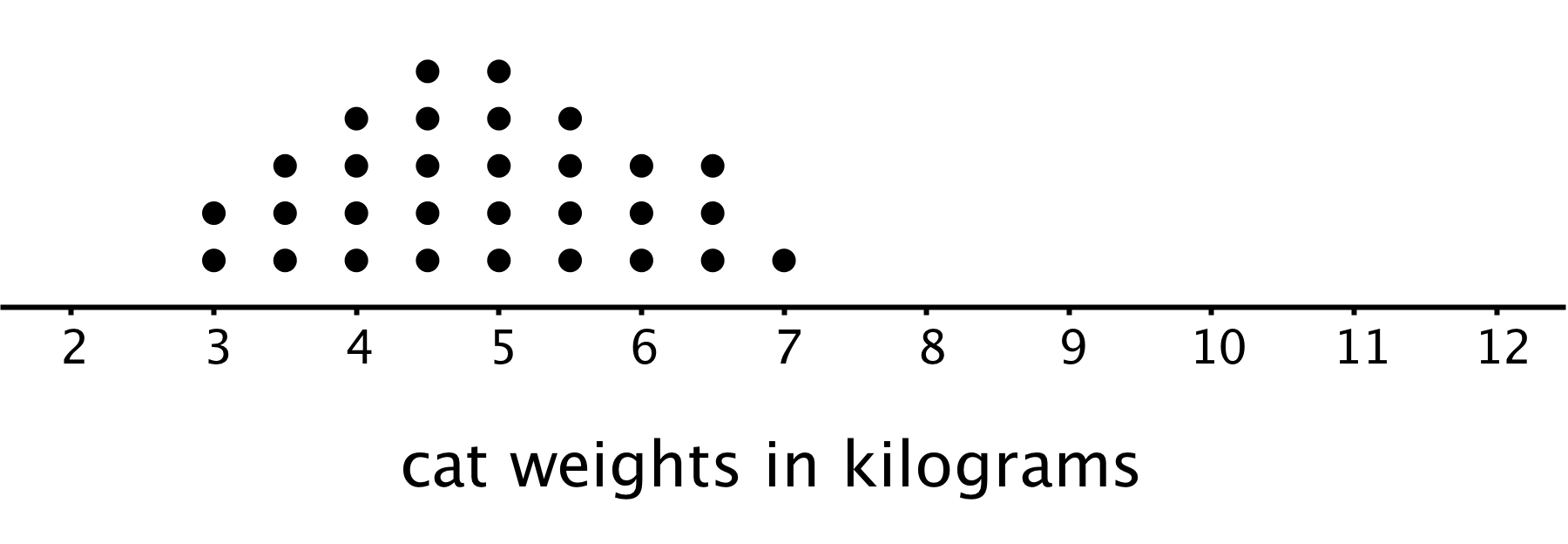

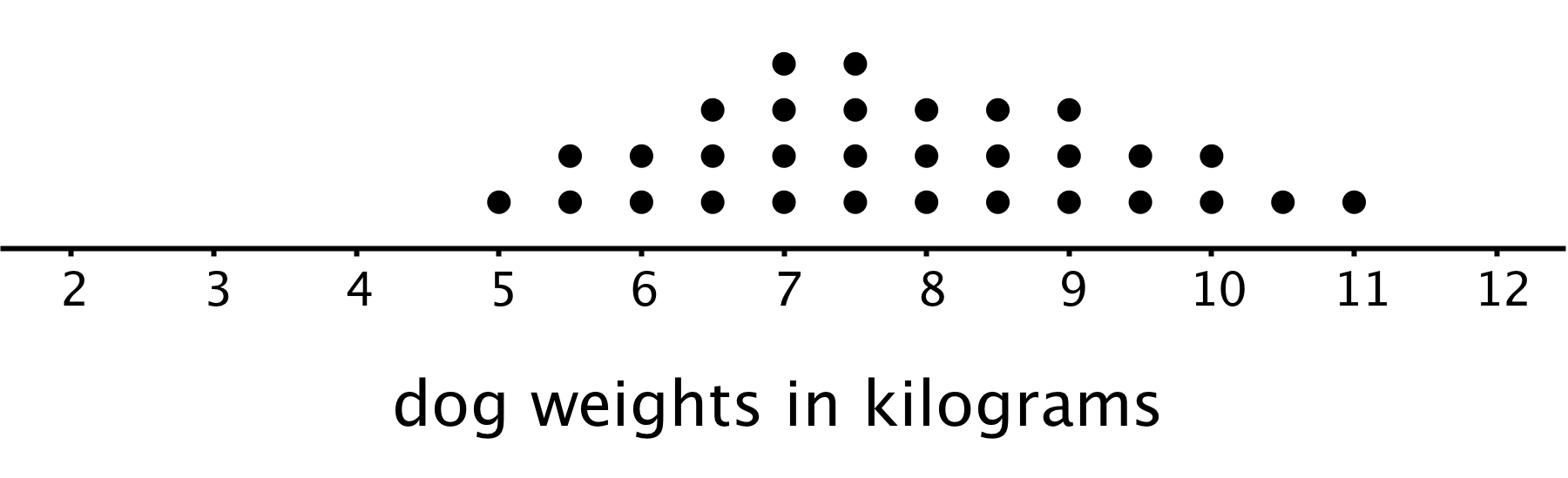

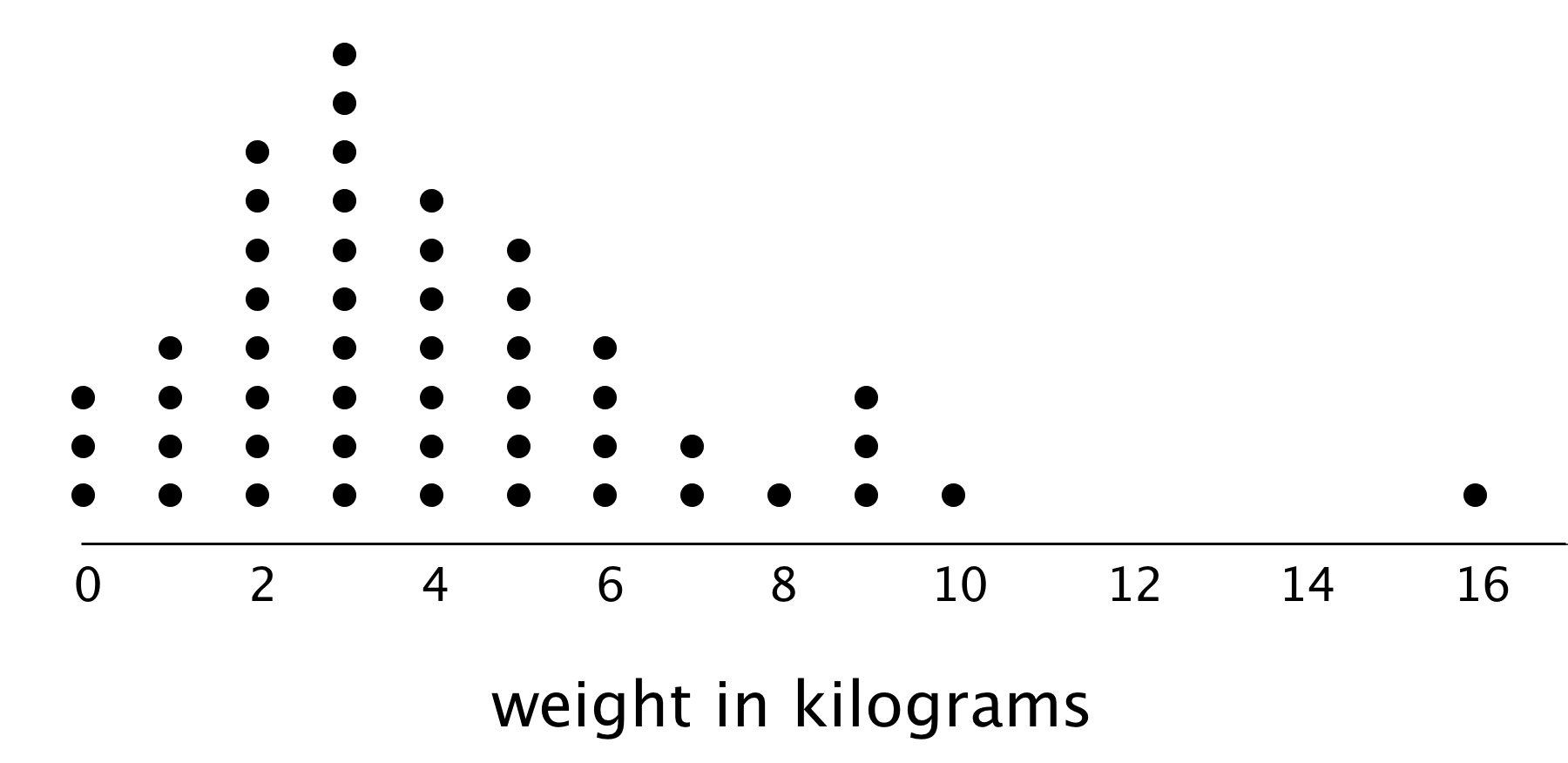

This dot plot shows the weights of backpacks, in kilograms, of 50 sixth-grade students at a school in New Zealand.

- The dot plot shows several dots at 0 kilograms. What could a value of 0 mean in this context?

-

Clare and Tyler studied the dot plot.

- Clare said, “I think we can use 3 kilograms to describe a typical backpack weight of the group because it represents 20%—or the largest portion—of the data.”

-

Tyler disagreed and said, “I think 3 kilograms is too low to describe a typical weight. Half of the dots are for backpacks that are heavier than 3 kilograms, so I would use a larger value.”

Do you agree with either of them? Explain your reasoning.